Flying on the Road: The Fascinating History of Motorcycle Riders in America

Table Of Contents

We know what a motorcycle can mean to someone—the open road, the freedom of exploration, the thrill of adventure just around the next corner. The feeling of the wind and sun on your skin as you race around mountains and through deserts is one that can’t easily be described.

Yet motorcycles, and those who ride them, haven’t always been welcomed with the most open of arms. Even today, motorcyclists are subjected to road discrimination and negative attitudes from insurance companies. The backstory as to why motorcyclists in America have been considered “hooligans” and “thugs” is more complicated than you might think. Read on to learn about the interesting history of motorcycles and their riders in America.

Despite the “bad biker” rep, two world wars, and a depression, the spirit of motorcycle culture is still thriving. As more people discover their love of off-roading, competitions, or even just a midnight ride, the culture around motorcycles continues to inspire.

How Motorcycles Created a Community

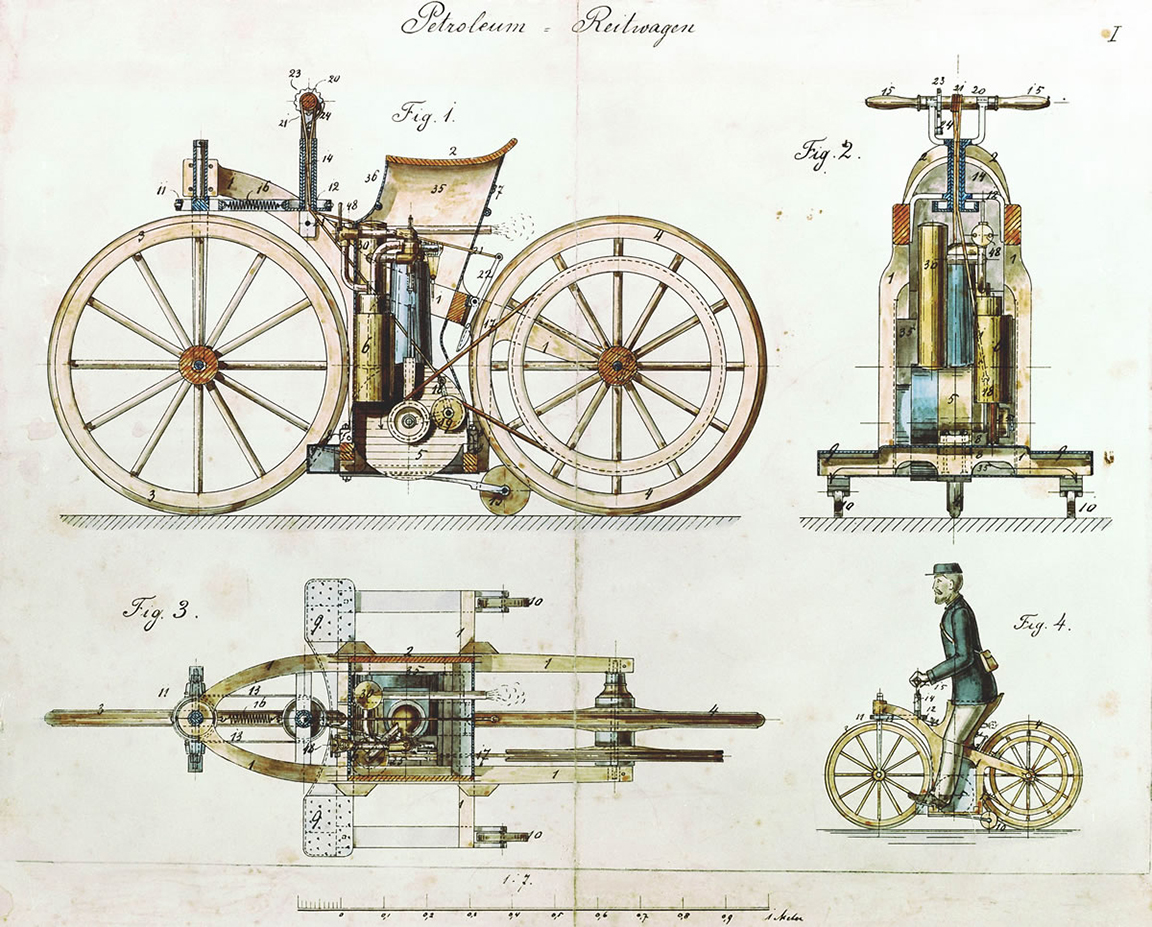

Developed by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach in late 1880s Germany, the first “motorcycle” was more of a piglet than a hog.

Described as looking like an “instrument of torture,” the motorcycle took time to develop into what it is today. Even still, the concept of a motorized bike took off quickly. People soon loved the friendly price point, speedy travel, and stylish aesthetic.

Soon, a flurry of American companies were inspired. Just a few years into the new century, the titans of motorcycle production were born: first Metz, then Indian Motorcycle (originally Hendee Manufacturing Company), and, of course, Harley-Davidson. As more people began riding motorcycles, bikers began forming clubs and hosting competitions. Groups of under-represented motorcycle lovers like women and African Americans also gathered together to ride.

In 1903, clubs were popping up around the country to discuss the rights of the road. George Hendee, founder of Indian Motorcycle, was a chairman of many such meetings, advocating for the formation of a real community around motorcycles. Eventually, they formed the first official organization: Federation of American Motorcyclists (FAM).

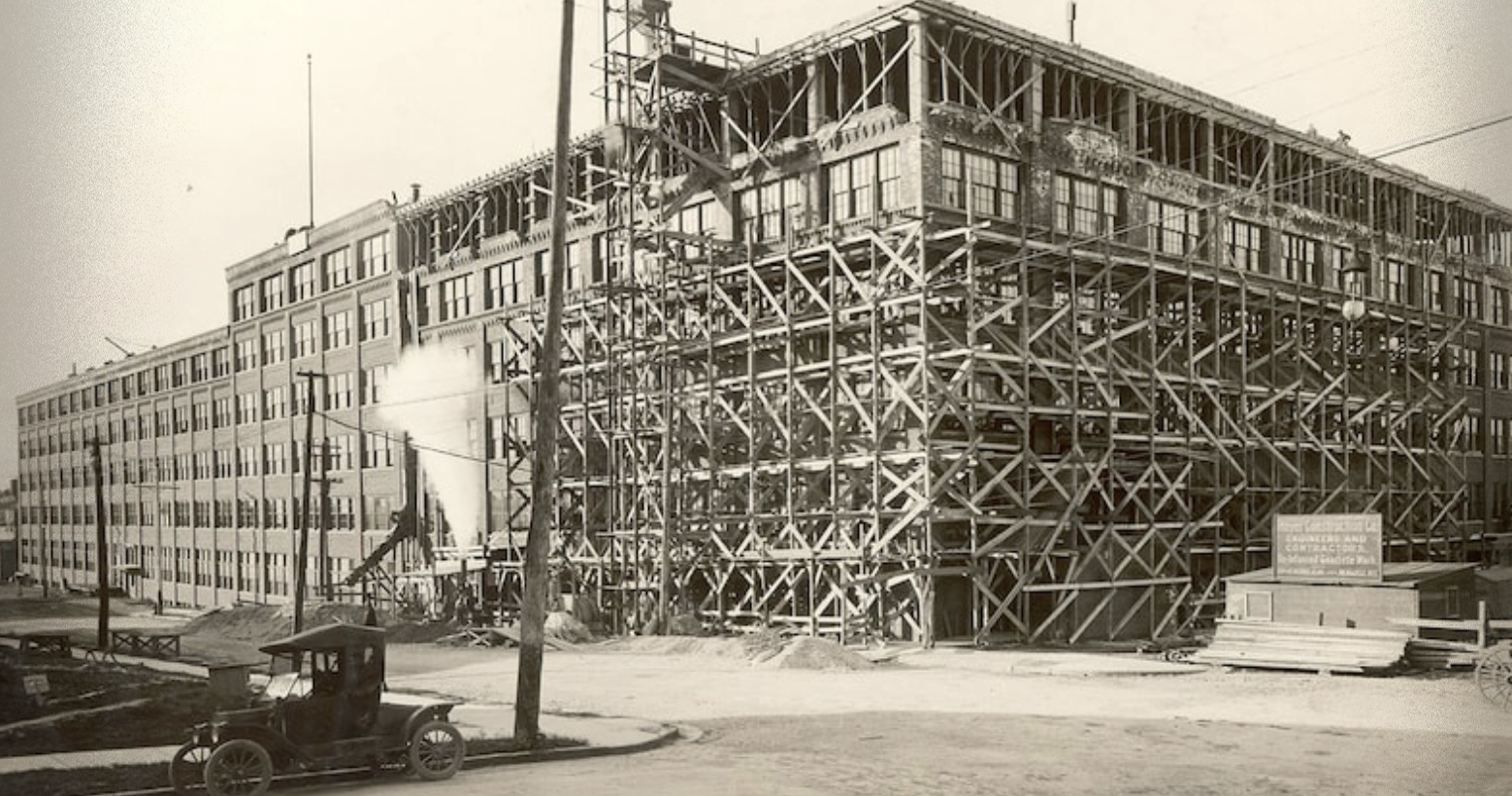

Harley-Davidson Motor Company, Milwaukee, 1910s

However, it wasn’t until WWI broke out that the motorcycle companies really began to rev up production. By the time the war was in full swing, both Indian and Harley-Davidson were contributing at least half their production to the war effort. By the end of the 1920s, Harley-Davidson had grown almost 300% and was the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world. Notably, Harley-Davidson also started a service school to train army mechanics.

Even though most motorcycle activities were canceled during the war, a majority of production was dedicated to combat, and a significant portion of the population was gone or injured from action, the love of motorcycles kept the culture alive. The FAM eventually collapsed, but other organizations survived. After WWI ended, the Motorcycle & Allied Trades Association (M&ATA) began recognizing competitions, clubs, and other activities. As interest grew, the American Motorcycle Association was formed in 1924 and headquartered in Chicago. The AMA still exists today and is the definitive leader of the industry.

Motorcycles Win the War—and a Following

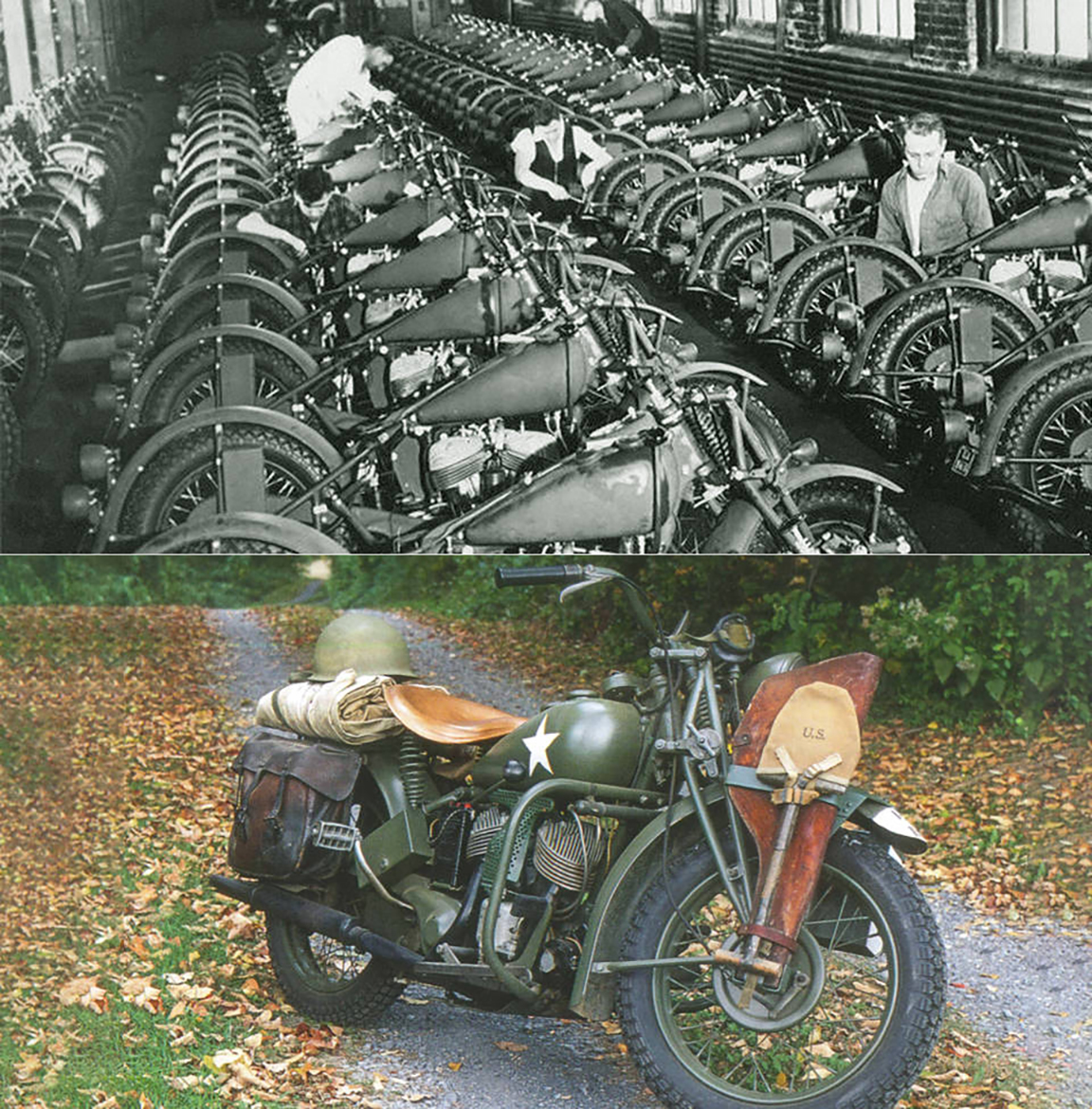

Motorcycle culture has endured because, even during wartime chaos, they stirred the imagination. As Britain churned out bike after bike for the war effort, each one had a more dazzling name than the last. Names like the Norton Commando, the Vincent Black Shadow, the Velocette Venom, the Ariel Red Hunter, and the Royal Enfield Bullet weren’t just created for the sake of making a sale. Instead, these flashy titles offered a chance of fantastic survival in the face of evil.

Poet, essayist, and motorcycle enthusiast Melissa Holbrook writes: “The motorcycle offered…a sort of stab at immortality: these man-made creations were constructed so that on them we could forget the sadness of not having been born this mighty…Although we made them, they make us fly.”

Indian Motorcycles for the warfront

However, these brave names did little to protect soldiers during combat, and the idea of a happy-go-lucky motorcyclist didn’t last long. Many vets were haunted by their time of service. A haven for battered and haunted soldiers, motorcycle clubs offered the same sort of togetherness vets may have shared with their comrades overseas. The horrors of war disillusioned many of them, leading them to wonder if a different world was possible.

Whatever the reason, the biking community continued to grow. It wasn’t until the summer of 1947 that the community changed forever.

Motorcycle Culture: The Twists and Turns

While not quite yet reaching outlaw status, bikers were beginning to develop into a more mischievous presence. In 1946, just a couple of months after the second world war ended, the infamous Boozefighters penned their club requirements:

- Get drunk at a race meet or cycle dance.

- Throw a lemon pie in each other’s faces.

- Bring out a douche bag where it will embarrass all the women (then drink wine out of it).

- Get down and lay on the dance floor.

- Wash your socks in a coffee urn.

- Eat live goldfish.

- Then, when blind drunk, trust me (Kokomo) to shoot beer bottles off your heads with my .22.

Certainly not anyone’s Sunday best, but they weren’t advocating for complete destruction. It wasn’t until the next summer that motorcycle culture was altered forever—and not necessarily for the best.

Prior to WWII, the AMA had started their still-popular Gypsy Tours. These were the biggest motorcycle events of the year and continue to offer an incredible three-day motorcycling experience. By 1925, the tours had been so successful that the AMA was hosting over two hundred of them. But when the war broke out, the tours were canceled like most motorcycle activities.

But in July 1947, the Gypsy Tours were back on. Almost 4,000 people drove their bikes to the small California town of Hollister. Perhaps more important than the actual event was the reporting of the event. While an event of that size (especially right after the war ended) was expected to be a bit wild, the story told in Life magazine depicted something much more intense.

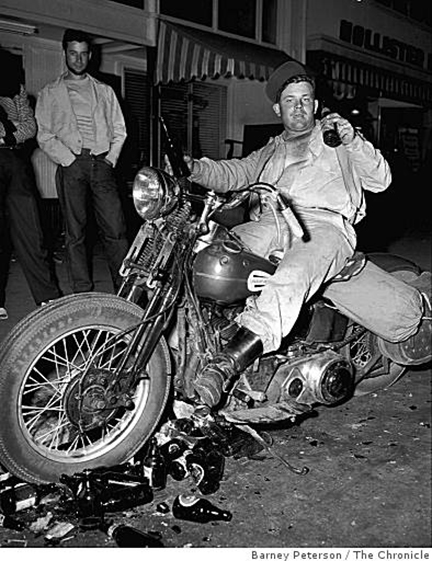

A photo from the Hollister Riot, 1947

This photograph in particular sparked outrage from motorcyclists, lawmakers, and journalists alike. Published in Life magazine, the article accompanying it was even more incendiary. Although brief, the article claimed that motorcyclists had essentially ransacked the entire town by breaking into bars, drinking publicly, and riding their motorcycles absolutely everywhere. The coverage even claimed that police arrived in riot gear and martial law became necessary.

With a circulation of almost five million people, the article was highly influential.

Almost immediately, the AMA attempted to reassure the American public that motorcyclists were not the wild drunks who were featured in Life magazine. Famously, the organization stressed that “99% of motorcyclists were law-abiding citizens.” They also revised their policy regarding clubs. Motorcycle groups now had to follow rules and register in order to be recognized, and every other group was automatically considered “outlaw.” While the intention of the statement may have been to take control of the situation, it really just created a space where those non-law-abiding riders could thrive. The backlash of this statement resulted in a rise of “1%” motorcycle clubs, which were the self-billed 1% of non-law-abiding citizens.

However, a recent investigation by the International Journal of Motorcycle Studies revealed the long-buried truth.

During the time, journalism was not necessarily the fact-checking machine that it aspires to be today. Sensationalism and storytelling held more weight than the actual truth. After the constant stream of news from WWII, newspapers were a ghost town in the summer of ‘47. Magazines that had previously flown off the shelves were now sitting in stores, just waiting to be turned into pulp. In short, journalism was in a crisis.

The two newspapers that “covered” the tour were engaged in fierce competition over readership. While the tour did have higher-than-usual attendance, the “chaos” described in the article was mostly inaccurate. Although the photo above might seem obviously staged, it did nothing to protect the reputation of motorcyclists. Instead, the article created a damaging reputation that has still prevailed—even almost a century later.

By the time the 60s rolled around, the image of an outlaw biker was popularized in the media. Movies and shows like The Wild Ones (which depicted the Hollister riots), Any Given Sunday, and Easy Rider worked to cement the reputation of “bad” bikers. In combination with Hunter S. Thompson’s grisly account of the Hells Angels and the tragic events of the Altamont Free Concert, motorcycling had been permanently linked to crime

Hits: 671