North American X-15: Setting the Pace for Manned Rocket Planes

Breaking Barriers: The Legacy of the X-15 Rocket Plane

Even in the late 1940s, when aviation was still in its infancy, visionary aircraft designers dared to dream of pushing the boundaries of speed, aiming to breach the sound barrier and go far beyond. One such daring endeavor was the Douglas X-3 Stiletto.

The X-3 Stiletto was an audacious project intended to achieve double the speed of sound, a remarkable feat for the early 1950s. However, just two years later, in December 1954, the aerospace community issued a request for proposals that laid out specifications for an aircraft that would test a new engine type, reach speeds beyond Mach 5, and explore altitudes never before ventured by any aircraft.

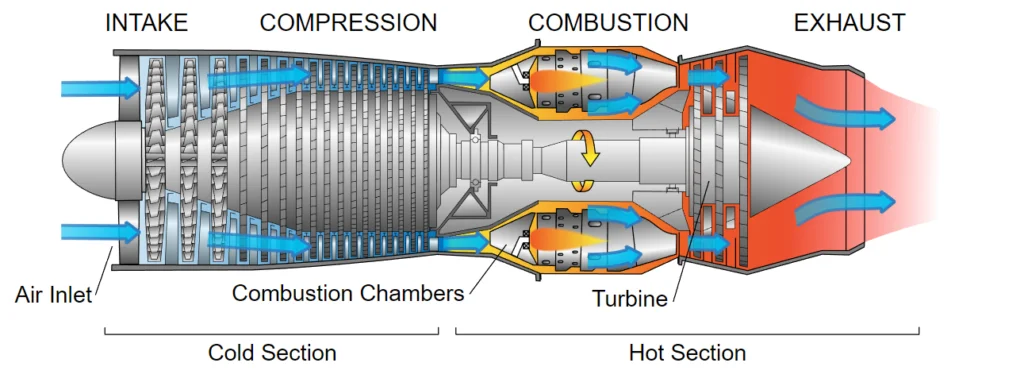

The challenge lay in the limitations of early jet engines, which lacked the power to propel even small, lightweight aircraft beyond Mach 2. To simplify, a turbojet engine ingests air, mixes it with fuel, and generates thrust. These engines are tuned to perform optimally at specific altitudes to achieve peak performance.

Yet, an aircraft’s top speed is also affected by another crucial factor: drag, or air resistance. As you increase your speed, the air resists your movement more vigorously. This phenomenon is apparent when you stick your hand out of a moving car window – you can feel the air pressing against it. Consequently, even modern jet fighters cannot reach their claimed top speeds at low altitudes due to this resistance.

However, as you ascend in the atmosphere, the air becomes thinner, reducing resistance and allowing for easier travel. On the flip side, jet engines require air to produce thrust, so flying too high can lead to a significant drop in engine performance.

To counter this lack of air at extreme altitudes, rocket motors come into play. Rockets burn fuel without relying on atmospheric oxygen; instead, they carry the necessary oxygen in liquid form. The higher you go, the faster you can potentially travel.

The pioneering Heinkel He-176 and the iconic Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet were among the early rocket-powered aircraft that set speed records. The Me-163 Komet, in particular, achieved an unofficial flight speed record of 700 mph in testing, which remained unchallenged until 1953.

Post-World War II, the pursuit of cutting-edge technology led to the development of rocket-powered aircraft that could potentially provide an edge in future conflicts.

In 1955, North American (NA) was awarded the contract to design the airframe of the X-15, while Reaction Motors was tasked with building its engines. Only four years later, in June 1959, the X-15 took its maiden flight.

Unlike conventional aircraft, the X-15 was never meant to take off under its own power. Instead, like other experimental aircraft such as the M2-F3 Lifting Body, it was designed to be carried aloft by a “mothership.”

NACA/NASA utilized an aging B-52A aircraft, retired in 1969, and a modified B-52B, both equipped with a pylon on the right wing to carry test vehicles. These were designated NB-52A “The High and Mighty One” and NB-52B “Balls 8.”

“Balls 8” first took flight in June 1955 and remained in service until December 2004, making it the oldest operational B-52 model at the time.

The X-15’s design had to accommodate its transport beneath the wing of a B-52, resulting in a relatively compact aircraft. It was built to accommodate a single crew member and had a length of just 50 feet 9 inches and a wingspan of only 22 feet 4 inches.

The X-15, despite its modest size, possessed a sleek, high-performance profile intended to achieve hypersonic speeds, defined as anything exceeding 3,836 mph or Mach 5.

Three X-15 aircraft were constructed: X-15-1, -2, and -3. Each contributed to a varying number of flights, with X-15-1 undertaking a total of 81 flights, while X-15-2 completed 53.

Tragically, during its 65th flight test in 1967, X-15-3 spun out of control at hypersonic speeds during descent, breaking apart and scattering wreckage over 50 square miles. The pilot, Michael Adams, lost his life in the accident.

Another accident occurred when X-15-2 crashed upon landing in 1962, causing significant damage. Following extensive repairs, it was modified to carry liquid hydrogen, received a 2.4-foot fuselage extension, and was equipped with auxiliary fuel tanks for extended range.

The X-15’s power plant was a critical consideration in its initial designs, as the aircraft had to be engineered around two XLR11 rocket motors and the necessary fuel tanks to propel it to the edge of space. All aspects of the design were geared towards making the X-15 the fastest and highest-flying aircraft ever.

The XLR11 rocket, also used in the Bell X-1, produced 6,000 pounds of thrust. However, by the end of 1960, after only 24 flights, an incredible upgrade was introduced: the XLR99. This new rocket motor was nearly ten times more powerful per unit and was similar in size, delivering a staggering 57,000 pounds of thrust. It was used for the remainder of the X-15’s service life, achieved through the use of anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen.

Remarkably, the XLR99 could consume 15,000 pounds of fuel in just 80 seconds.

Despite the seemingly excessive fuel consumption, the X-15 achieved numerous astounding world records that remain unmatched to this day. In 1967, it reached a mind-boggling altitude of 102,000 feet, equivalent to 19.34 miles, and hit a top speed of 4,520 mph. To put this in perspective, the year 1967 marked the inaugural Super Bowl game.

Speed was not the X-15’s only impressive feature; it also set records for altitude. The highest known flight occurred in 1963 when test pilot Joseph Walker reached an altitude of 67 miles, exceeding 353,000 feet, at a speed of 3,794 mph (Mach 4.98). Any flights above 264,000 feet qualified the pilots as astronauts.

In conclusion, despite the tragic accident that claimed the life of Michael Adams during the X-15 program, the project, which spanned from 1955 to its final flight in October 1968, was a monumental success. It completed 199 flights, achieving some of the highest and fastest flights ever recorded.

Today, two surviving X-15s serve as museum pieces, reminding us of the incredible feats that humans can accomplish. The era between the end of World War II and the 1980s marked a golden age for aviation, during which astonishing advancements were made in a remarkably short period, forever changing the way we design aircraft.

Hits: 6